Many of us probably know that less sugar is likely better for our children. And we all know eating less sugar cannot be worse for our children.

It can seem like a battle sometimes, getting children to eat less sugar.

But in this article, I am going to share why reducing sugar in your child(ren)’s diet makes a difference and is worth the effort… and ideas for better options that can make a difference quickly.

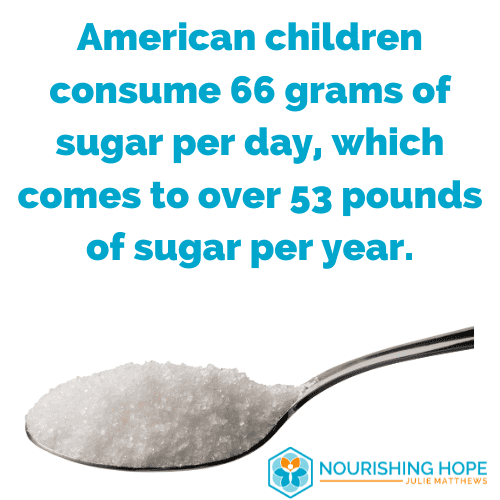

Children Consume More Than 3 Times the Recommended Amount of Sugar

One thing that is not up for debate is that many children in the United States (and many countries around the world) consume too much sugar daily.

American children consume 66 grams of sugar per day, which comes to over 65 pounds of sugar per year.[1] And a 2017 study estimated that Children in England consume half of their daily recommended sugar intake at breakfast by consuming sugary cereals and eating foods high in carbohydrates, and three times the recommended amount per day.[2]

American children consume 66 grams of sugar per day, which comes to over 65 pounds of sugar per year.[1] And a 2017 study estimated that Children in England consume half of their daily recommended sugar intake at breakfast by consuming sugary cereals and eating foods high in carbohydrates, and three times the recommended amount per day.[2]

Sugar-filled beverages account for a large amount of the sugar consumed. Sugar from drinks can add up quickly. And can come from sources that some people don’t think of as unhealthy as they might soda. For example, fruit juice, sports drinks, and non-dairy milk beverages contain around the same amount of sugar as soda. In a study from 2011-2014, 63% of children drank a sugary beverage on a given day. This equaled 143 calories from these beverages, from which virtually, if not, all of the calories came from sugar.[3]

In addition to leading to sugar crashes, sugar is often an empty calorie, meaning it provides no real nutrition for kids. This has led to experts including the American Heart Association to recommending that kids aged 2 to 18 consume no more than 25 grams or six teaspoons of sugar per day for overall health and well-being.[4]

In addition to leading to sugar crashes, sugar is often an empty calorie, meaning it provides no real nutrition for kids. This has led to experts including the American Heart Association to recommending that kids aged 2 to 18 consume no more than 25 grams or six teaspoons of sugar per day for overall health and well-being.[4]

Reducing Sugar Can Help in Just Days

Reducing sugar in a child’s diet can improve their health in only 9 days. In a study of children with obesity and metabolic syndrome, researchers created a diet containing the same levels of calories, fats, protein, and carbohydrates, where the only change was with a reduction in sugar from 28% to 10% (substituting starch for the sugar), and a decrease in fructose from 12% to 4 %. The diet resulted in a decrease in diastolic blood pressure, triglyceride level, LDL-cholesterol, and weight, as well as improvements in glucose tolerance and hyperinsulinemia (high insulin).[5]

This study demonstrates that sugar is metabolically harmful and contributes to metabolic syndrome, regardless of calories and obesity.

And the study shows that making changes to your child’s diet can make a big difference in their health, and after only a short time.

Limiting Sugar Improves Hyperactivity and ADHD

It may be more well understood that limiting sugar helps the body. But, can it also be helpful for things like mood and attention? Science has validated that reducing sugar intake can help improve not only physical health, but attention and mood too. In fact, some studies suggest that sugar can cause, or contribute to, hyperactivity and ADHD in children, proving that sugar can affect both the body and brain. But for parents this is great news!

By simply reducing sugar you can improve the health and brain function in your child… including for children with ADHD. If you want to learn more, I encourage you to read my article on 5 ways (and the research behind how) sugar causes hyperactivity and ADHD.

Are Artificial Sweeteners an Option?

No. Parents who are concerned about high blood sugar and hyperactivity in their children may consider using artificial sweeteners as a substitute; however, there is evidence to suggest that this is not a good idea, such as:

Effects on the Digestive System. Some studies have found that artificial sweeteners may disrupt the natural balance of healthy bacteria in the digestive system, and increase harmful microbes.[6] It is possible that this imbalance could impact the rest of the body, including the brain, further discouraging the addition of artificial sweeteners in a diet for children with ADHD.

Potential to Spark Cravings for Sugar. Scientists believe that consuming artificial sweeteners may cause a rise in insulin levels in the body, leading to sugar cravings. Although there is also conflicting evidence, some studies have found that people who consume artificial sweeteners are more likely to become obese.[7]

Excitotoxins. Some artificial sweeteners are neurotoxins and can cause excitability of brain cells causing neurological damage.[8]

Artificial sweeteners to avoid include aspartame (products such as Equal and Nutrasweet), sucralose (Splenda), saccharin (Sweet ‘N Low), and Acesulfame K (ACE).

Better Sugar Choices

After all of this information about sugar, the most common question I get is, “What is the best sugar?”

If you are going to eat sugar, or consume sweet treats, it’s good to know which sugars are better than others and why. Now before I give my answer, please note that ALL sugar can cause problems in excess. The secret is to limit sugary foods with your children (or yourself) and when you do consume them, choose the best you can.

There are two categories of sweeteners to discuss: natural sugars and natural sweeteners. Artificial sweeteners, as I mentioned above, have many challenges associated with them.

Natural sugars

Natural sugars are those that occur naturally and act like sugar in the body: they raise blood sugar levels and feed microorganisms. For these reasons, these sugars should be consumed in moderation.

Fruit

Fruit is a wonderful sweet treat to consume or use in desserts. It’s rich in vitamins, antioxidants, and fiber. The glycemic index and glycemic load of most fresh fruit is low (or medium in some cases). In other words, fruit does not raise blood sugar rapidly like table sugar/sucrose does. However, do be aware that fruit is high in fructose, and fructose can be harmful when consumed in large quantities. Fortunately, fresh fruit’s high fiber and water content makes it filling and it’s not difficult to consume in moderation.

Coconut sugar

Coconut sugar is derived from coconut and contains some vitamins, minerals, and antioxidants. Coconut sugar is also one of the granulated sugars lowest in glycemic index. Coconut sugar has a one to one replacement with regular white sugar in recipes. Coconut sugar is also less refined so it has a rich brown sugar type flavor.

Raw honey

Raw honey is another natural sweetener that has nutrients and health benefits. It contains vitamins, minerals, and antioxidants including riboflavin, B6, iron, zinc, potassium, and manganese. Locally sourced, raw honey also helps support our health against allergies, as the local honey contains small amounts of pollen that helps our body adapt. Honey is allowed on the Specific Carbohydrate Diet and the GAPS diet, when many other sugars (except fruit) are not. Honey is sweeter than sugar (about 25% sweeter) so when substituting it you will likely need less honey than the recipe calls for.

Natural sweeteners

Stevia

Stevia is a non-sugar natural sweetener. In other words, it does not raise blood sugar (glycemic index of 0) and it does not feed microorganisms like candida. It is derived from the leaves of the stevia plant and has zero calories. It is not fermentable so it typically does not create digestive problems. It is very concentrated in sweetness, being 50-300 times sweeter than sugar so the proportions will be different for a recipe which often requires specific recipes to get the proportions correct, unless it’s being added to a beverage such as a smoothie or hot chocolate where proportions are not an issue.

Studies on stevia show that it has properties that are antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, anti-high blood pressure, anti-obesity, anti-diabetic, anti-cancer, and antimicrobial, and stevia reduces intake of food and reduces total cholesterol, LDL-cholesterol, and triglycerides.[9]

Monk fruit

Monk fruit, also known as luo han guo, is also a non-sugar natural sweetener. The mogrosides in monk fruit, a glycoside that give it it’s sweet flavor have been shown in studies to have antioxidant and antidiabetic properties.[10] Monk fruit, like stevia, is very sweet, about 200 times as sweet as sugar and as such usually requires special recipes for it. Monk fruit has a glycemic index of zero and no calories. It also does not feed yeast.

Erythritol

Erythritol is a sugar alcohol, or polyol, which is a type of FODMAP (fermentable carbohydrate), that does not have an effect on blood glucose levels or insulin levels and has close to zero calories.[11] Since, erythritol is a sugar alcohol and can cause gas and digestive upset, so it’s best to proceed slowly. However, unlike other polyols, it is absorb through the small intestine, so it does not cause as much digestive upset for most people.[12] Erythritol is not systemically metabolized and is excreted in the urine unchanged, and it improves oral health by reducing plaque and dental caries (cavities).[13] Studies on erythritol also show it has antioxidant properties and in type 2 diabetes may improve endothelial function.[14] Erythritol is about 70% as sweet as sugar, so it can often be substituted in recipes (though the amount may need to be adjusted).

Lakanto and Erythritol Blends

Erythritol is often blended with monk fruit or stevia to create a 1:1 sugar substitute.

Lakanto is one of my favorites. Lakanto is a combination of monk fruit and erythritol and is able to be used in recipes one for one. In other words, one cup of sugar would be substituted for 1 cup of Lakanto. This makes it easier to be used in recipes.

While these “non-nutritive” sweeteners seem to have good studies behind them, I still think it’s prudent to use moderation with any foods that are consumed more than was intended by nature.

Play around with one sweetener and see what your child thinks, you can also combine these where needed. For example, sometimes I combine fruit and then add in some additional stevia (for example in a smoothie) or cut the sugar in half in a recipe and then add in some stevia to give it the desired sweetness. This will reduce the sugar content.

Limit Sugar

While the average child eats over 3 times the recommended amount of sugar each day, with a few easy changes a parent can reduce sugar fairly simply. A soda, sports drink, and fruit juice have 32-52 grams of sugar in a 20 ounce bottle, when someone consumes these drinks they often get a lot of sugar this way. So just avoiding one or two drinks a day can make all the difference with keeping sugar in the recommended zone.

To keep sugar to less than 25 grams per day as recommended by experts, I like to recommend to my Nourishing Hope Families that they set a guideline for treats of 5 grams of sugar per serving. This allows kids to see how much sugar is in some of their favorite foods. This is a great way to help kids read labels, learn about portion sizes, and take charge of their nutrition at an early age. A treat might end up being over 5 grams, but it can become a discussion and a learning opportunity with your child.

Conclusion

Reducing sugar does matter. And the great news is that you can make changes anytime that can help right away.

And decreasing the sugar in your child’s diet doesn’t have to take the fun (or taste) out of treats. There are many options that are either lower sugar or no sugar that can be wonderful substitutes, if you know what to use. The key is to just start somewhere!

Give it some time. Kids (and adults) need time for their palette to change. In a short while, they will become more sensitive to naturally sweet foods, and they’ll find moderately sweet foods a wonderful treat!

Life is about balance and normally if your child gets some sugar, it is not the end of the world. But reducing sugar can be an important way to find more dietary balance around sugar.

And if you have a child who reacts poorly to sugar or who has underlying health issues and needs to restrict sugar, knowing these alternatives can be powerful and critical for their health or healing journey.

0 Comments