The microbiome in autism is an avenue of important research. Studying the differences in microbiome composition for individuals with an autism diagnosis is yielding valuable insight. Here’s some recent research on the microbiome and children’s health, including kids with autism.

The microbiome in autism is different and research is being done to determine why and how to improve autism by addressing it.

Over my 2 decades in the autism community, I’ve seen the interplay between restrictive diets and lack of microbiome diversity but also the profound changes that can occur when dietary shifts happen that also impact the microbiome positively.

If you saw the recent study published in Cell Press[1] by Yap, et al., you may be interested in the research, but also a bit disappointed as I was.

“We found negligible direct associations between ASD diagnosis and the gut microbiome. Instead, our data support a model whereby ASD-related restricted interests are associated with less-diverse diet, and in turn reduced microbial taxonomic diversity and looser stool consistency.”

While this statement is not incorrect – diet could play a role in the microbiome changes – it is only part of the picture.

The researchers go on to say, “…the contribution of the microbiome to ASD is unconvincing.” This idea that the microbiome doesn’t play a role in the etiology of autism is premature. There is quite a bit of evidence to the contrary, including this study by Dr. MacFabe.[2] It is possible that part of the reason for the development of autism could be related to the microbiome. Certainly more research is needed before we can conclude the contrary.

Furthermore, their statement leads people to believe that the only factor in the different microbiome is related to diet.

There are a multitude of potential reasons that the microbiome may be different in autism. Could it be their immune system isn’t recognizing the microbes as pathogens? Are they not able to fight off the pathogens? Could it be the presence of more pathogens, such as clostridia?[3] Could it be the presence of different species than normal or less beneficial bacteria?[4] Do birth and delivery methods factor in? Does antibiotic use play a role?

Understanding that the microbiome is different and why is a first step. I appreciate that this study lays out one such reason and feel this does further our knowledge of autism and the microbiome. But it’s too quick to dismiss other factors and the two way interplay of diet and microbiome. It is not just a one way street.

Additionally, the significance of this difference in microbiome is minimized in its potential to cause both digestive conditions and autism severity.

Early Microbiome Impact on Autism

I believe there to be substantial evidence that the microbiome can be a driving role in autism, including starting with the mother’s microbiome.

Cutting-edge research suggests that even mother’s gut health during pregnancy plays a critical role in determining the child’s risk of developing ASD.

Researchers hypothesized that, in mice, interleukin-17a (IL-17a), a molecule produced by the immune system, could trigger ASD-like behaviors.[5] [6] [7]

Probiotic Options in Autism

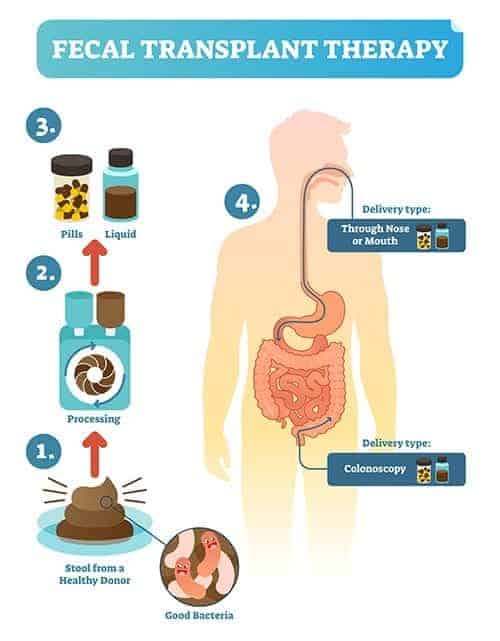

The topic of probiotics and autism is a large and well established one. Whether we are discussing traditional probiotic supplements, prebiotics or probiotic foods, or even fecal transplants, the research continues to show that as the microbiome shifts, individuals with autism may lessen and/or eliminate the behavioral markers that determine their autism diagnosis.

The topic of probiotics and autism is a large and well established one. Whether we are discussing traditional probiotic supplements, prebiotics or probiotic foods, or even fecal transplants, the research continues to show that as the microbiome shifts, individuals with autism may lessen and/or eliminate the behavioral markers that determine their autism diagnosis.

And this is not just seen in the autism population. Research has validated this same idea – adjusting the microbiome results in improvements in[8]:

- Global mood

- Vigor

- Depression

- Tension

- Fatigue

- Confusion

- Anger

What goes on in the gut impacts mood and behavior.

Companies like Sun Genomic are actively looking at the makeup of the microbiome via stool samples and creating custom blends of probiotics based on bioindividual need.

While it is true that the research on positive results of probiotics on autism is mixed, the microbiome’s role in autism is more clear.

Fecal Transplants

Unfortunately, individuals with autism can face overgrowth of pathogenic bacteria, including clostridia, as well as a generalized disrupted microbiome.

With the emergence and prevalence of persistent infections such as Clostridium difficile, traditional approaches including antibiotics are becoming limited and ineffectual. Fecal transplants on the other hand are being shown as quite effective against this type of infection.[9]

Even if the individual does not have Clostridium difficile, fecal transplants are showing great promise in research settings with persistent GI conditions such as constipation, diarrhea, indigestion, and abdominal pain. For individuals with autism, this study found not only an improvement in GI symptoms but a reduction in autism symptoms as well.[10]

Even if the individual does not have Clostridium difficile, fecal transplants are showing great promise in research settings with persistent GI conditions such as constipation, diarrhea, indigestion, and abdominal pain. For individuals with autism, this study found not only an improvement in GI symptoms but a reduction in autism symptoms as well.[10]

As a result of that study, it prompted me to write this article on Fecal Transplant for Autism: What We Know (& What We Don’t).

The fecal transplant studies in autism found an 80% decrease in gastrointestinal problems. By week eight, there was a 25% reduction in ASD symptoms. And the benefits continued. At two years participants had a 45% reduction in ASD symptoms. And 44% of children originally diagnosed with ASD were now below the cutoff for an autism diagnosis.

I was disappointed that this fecal transplant research was dismissed by researchers in this new microbiome and diet study (Yap, et al., 20211).

Downplaying the Importance

And what was even more disheartening were these additional comments:

“Families are desperately seeking new ways to support their child’s development and wellbeing. Sometimes that strong desire can lead them to diet or biological therapies that have no basis in scientific evidence,” Professor Whitehouse said.

“The findings of this study provide clear evidence that we need to help support families at mealtimes, rather than trying fad diets. This is a hugely important finding.”

Equating therapeutic diets that parents are doing to help their child feel better with “fad” diets is dismissive, and frankly insulting.

Seeing clients one on one, running my nutrition program for parents, and training practitioners through my BioIndividual Nutrition Institute has shown me quite clearly that diet can help improve health and autism symptoms, as well as diet affects the microbiome which in turn affects behavior.

And, not only have I seen the impact of these things (diet’s impact on microbiome and vice versa) scientific research also validates that.

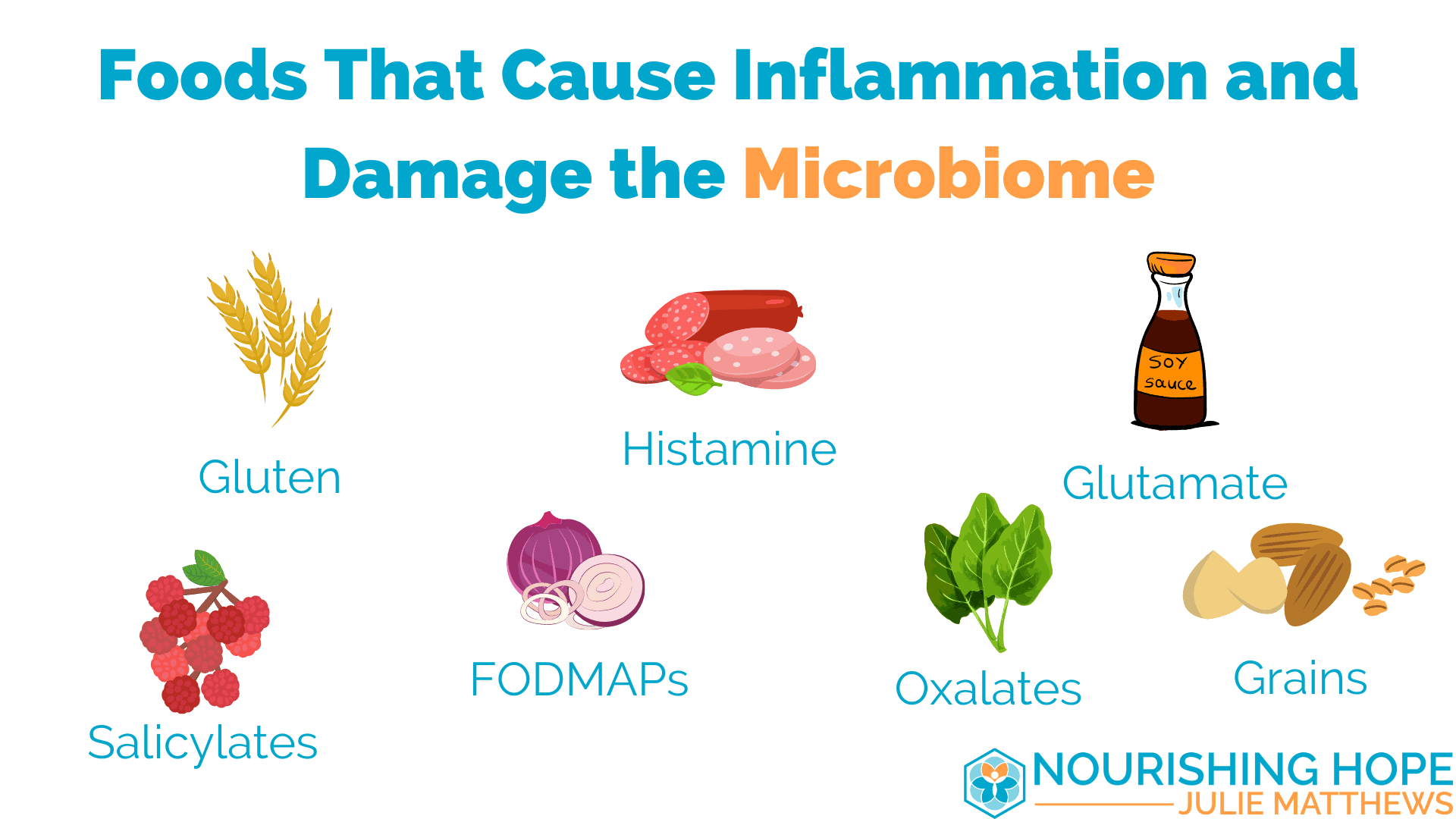

For individuals with Celiac Disease (CD) or non-Celiac gluten or wheat sensitivity, this study showed that a gluten-free diet “evoked a positive effect on gastrointestinal symptoms by helping to restore the microbiota population and by lowering pro-inflammatory species.”[11]

And in regards to diet in microbiome composition, one review concluded, “the literature suggests that diet can modify the intestinal microbiome, which in turn has a profound impact on overall health.”[12]

What is also important to consider is the effect of dysbiotic factors like yeast/bacterial/parasitic overgrowth on dietary choices. If you see clients with severe gut dysbiosis who talk about food cravings, it is not just lack of willpower. We see children who will self-select the foods that are contributing to the dysbiotic overgrowth.

In fact, this study concludes that: “Evolutionary conflict between the host and microbiota may lead to cravings and cognitive conflict with regard to food choice.”[13]

Conclusion

I do agree with researchers in this study that picky eating can negatively affect food choices and the microbiome. And I think it’s interesting that they found that diet affects the microbiome in children with autism. So, it’s important to help them make good choices that will help their health and microbiome.

But it’s also important that we do not conflate poor diets from picky eating with parents putting their child on a therapeutic diet in an attempt to help them improve. Furthermore, we should not assume this therapeutic diet is chosen because it’s a “fad.” Many parents do a lot of research and spend a great deal of time choosing a diet intelligently and strategically.

I also think the role of the microbiome as a factor in autism severity, and even its etiology, needs to be researched further.

Next Steps

Are you intrigued by how diet can shape your child’s microbiome and as a result their behavior? If you are new to nutritional intervention, I invite you to download my free guide, 12 Nutritional Steps to Better Health, Learning and Behavior. Thousands of families just like yours have used my free guide to get started on the nutritional changes that would spark incredible changes in their children.

0 Comments